Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Some Initial Notes

Drone functionalities can be classified to include (Al-Dhaqm et al., 2021)

- the Ground-station controller,

- (multi)rotor system,

- on-board Flight Control Board (FCB),

- integrates and coordinates information from every functional unit of the drone

- Memory artifacts

- Electronic Speed Controller (ESC),

- Memory artifacts

- on-board Power Management System (PMS)

- Memory artifacts

- as well as the Transceiver Control Unit (TCU).

- Electromagnetic wave data

Complexity - drone forensics is more complicated because it needs to integrate multiple data types (Abdulrahman Debas, Albuali and Hafizur Rahman, 2024)

- Flight Logs

- GPS Coordinates

- Video and Audio Recordings

- Sensor Readings

- Telemetry Data

- Wireless Communication Logs

- Data Transmission Protocols

Drone Investigations Literature Review

Before creating a Standard Operating Procedure regarding the investigation of a drone, I conducted a literature review of several papers that discussed drone forensics and demonstrated various analytical frameworks as a reference for my procedure steps.

In ‘Research Challenges and Opportunities in Drone Forensics Models’ by Al-Dhaqm et al. 2021, many of the aspects of a drone forensic investigation were highlighted, specifically the artefacts that differ from a traditional forensic investigation such as Electromagnetic Wave Data taken from the Transciever Control Unit (TCU) and the reliance on volatile memory over non-volatile. Typical forensic software may not be prepared to handle this data.

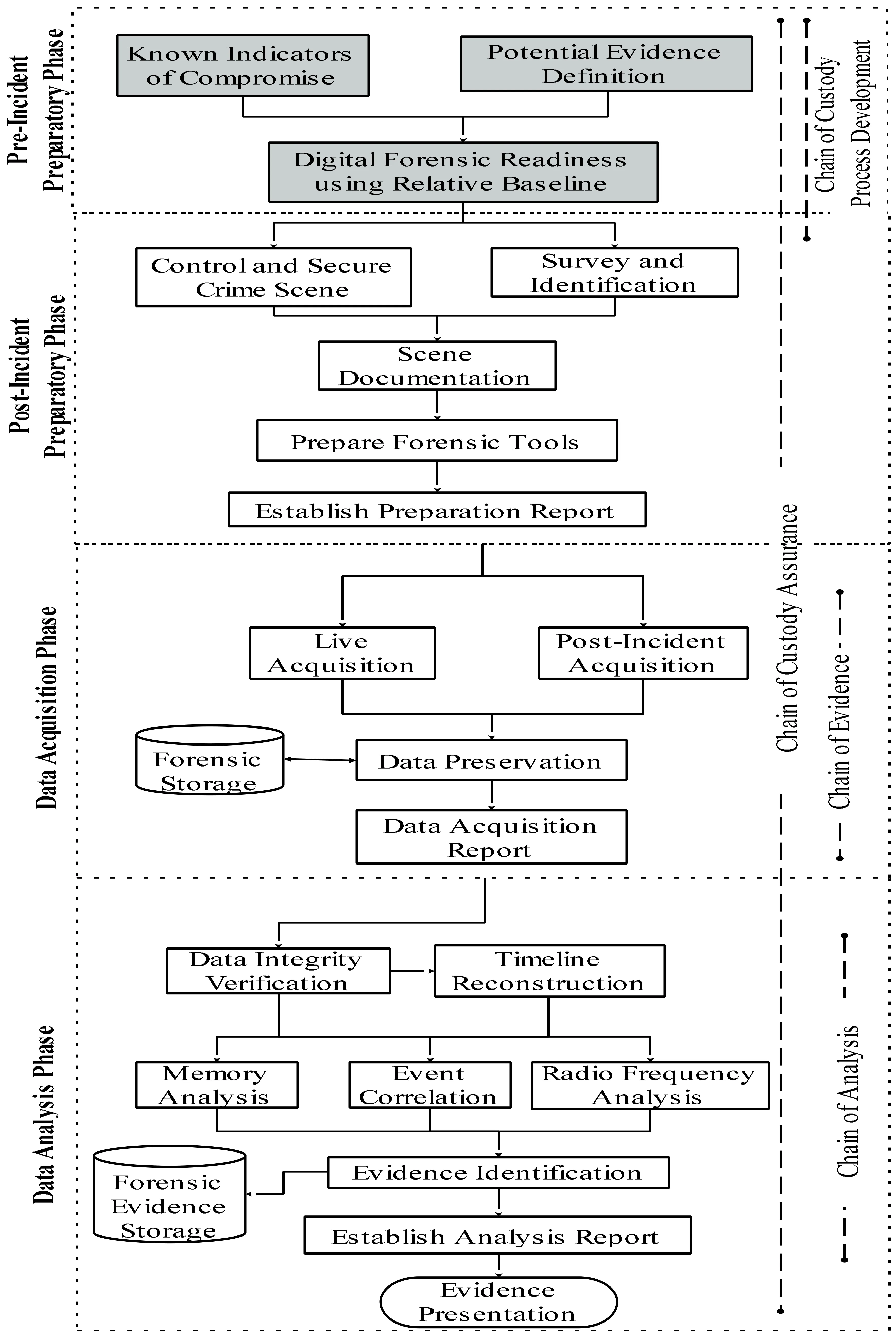

An Integrated UAV forensic investigation model is provided, which breaks the investigation down into four stages: Pre-incident Preparatory Phase; Post-Incident Preparatory Phase; Data Acquisition Phase; and Data Analysis Phase. This model could be a good framework to base the steps of a SOP on.

Figure 1: Integrated UAV Forensic Investigation Model by Al-Dhaqm et al. 2021

Figure 1: Integrated UAV Forensic Investigation Model by Al-Dhaqm et al. 2021

‘Forensic Examination of Drones: A Comprehensive Study of Frameworks, Challenges, and Machine Learning Applications’ by Abdulrahman Debas, Albuali, and Hafizur Rahman 2024 provides a list of the different types of data that could provide indicators of compromise in an investigation and may be relevant for the investigator to look for. This includes things such as: Flight Logs; GPS Coordinates; Recordings; Telemetry Data; and more.

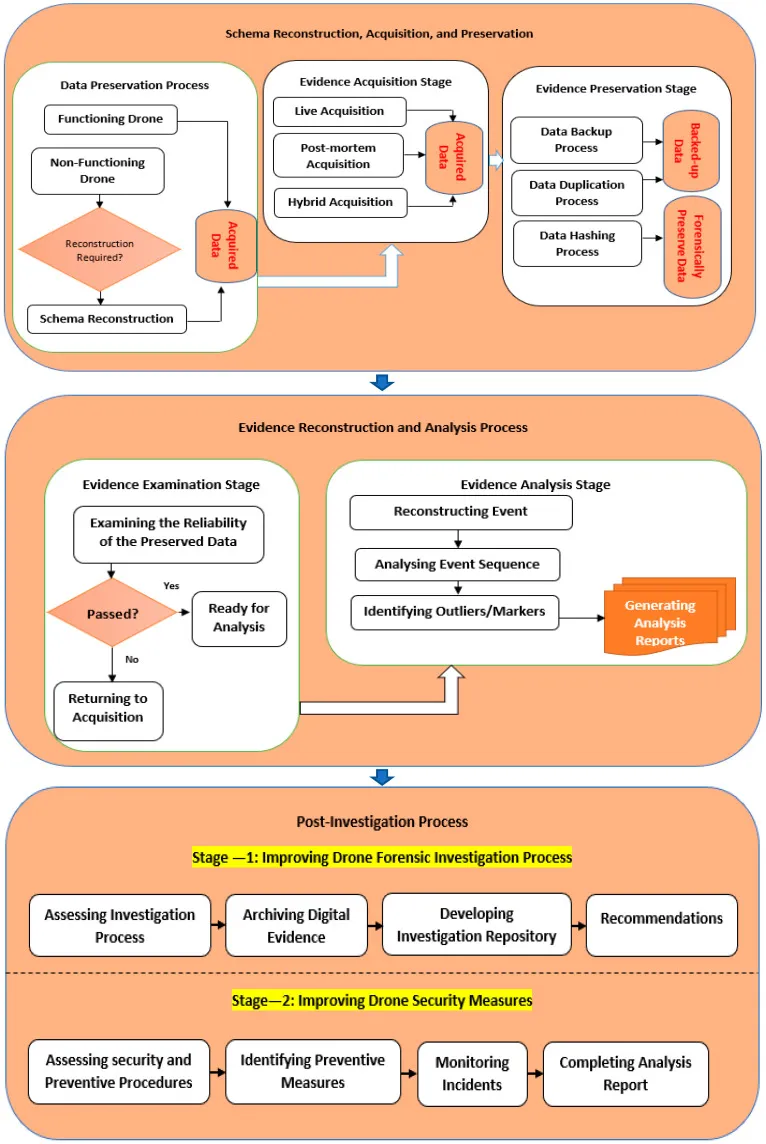

This paper also suggests multiple other forensic models for drone investigations. CCAFM (F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, Al-Otaibi, and Alsewari 2022) is described by the paper as “A Comprehensive Collection and Analysis Model […] encompassing three key processes: Acquisition and Presentation, Reconstruction and Analysis, and Post-investigation.” Another, the Drone Forensics Readiness Framework (DRFRF) (F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, and Al-Otaibi 2022), is described as “a novel contribution achieved through the design science method. This framework emphasizes proactive forensic readiness in the drone domain”.

CCAFM is discussed fully in ‘A Comprehensive Collection and Analysis Model for the Drone Forensics Field’ by F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, Al-Otaibi, and Alsewari 2022. This framework is in three parts: Schema Reconstruction, Acquisition, and Preservation; Evidence Reconstruction and Analysis Process; and Post Investigation Process. The inclusion of the post-investigation processes differentiates it from other models. It was developed by extracting the processes found in other models and organising them into a new framework. The features were organised into groups and stages to form an analysis model that could be broken down into steps in an SOP.

Figure 2: CCAFM (F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, Al-Otaibi, and Alsewari 2022)

DRFRF is developed in the paper ‘A Novel Forensic Readiness Framework Applicable to the Drone Forensics Field’ by F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, and Al-Otaibi 2022. This paper also identified the features present in other drone forensics models to create a framework. It divides the framework in two stages: the proactive forensics stage and the reactive forensics stage. The proactive stage divides into the Monitoring and Capturing Phase and the Preservation Phase. This involves collecting the data to be investigated and making sure nothing happens to change it. The reactive forensics stage is divided into the Examination and Analysis Process and the Documentation and Reporting Process. These four stages would make a good framework for a first-responder or investigator to follow, as it cleanly divides the responsibilties up with each stage and highlights the main goals of each.

.nO4i-Yrj_Z1PohF0.webp)

Figure 3: Drone Forensics Readiness Framework (F. M. Alotaibi, Al-Dhaqm, and Al-Otaibi 2022)

‘Drone Forensics: Challenges and New Insights’ by Bouafif et al. 2018 contains a discussion on the challenges specific to drone forensics due to the unique factors of drones. It considers the problem that data may be split over multiple locations such as the drone, radio controller, and server, and without all components it may be difficult to come to a a conclusion. There is also depth given into the problems with reading the internal memory of a drone, as there is no standardisation of firmware, and so standard format for protocols or flight data. The flight data is also often encrypted, creating more problems when investigating.

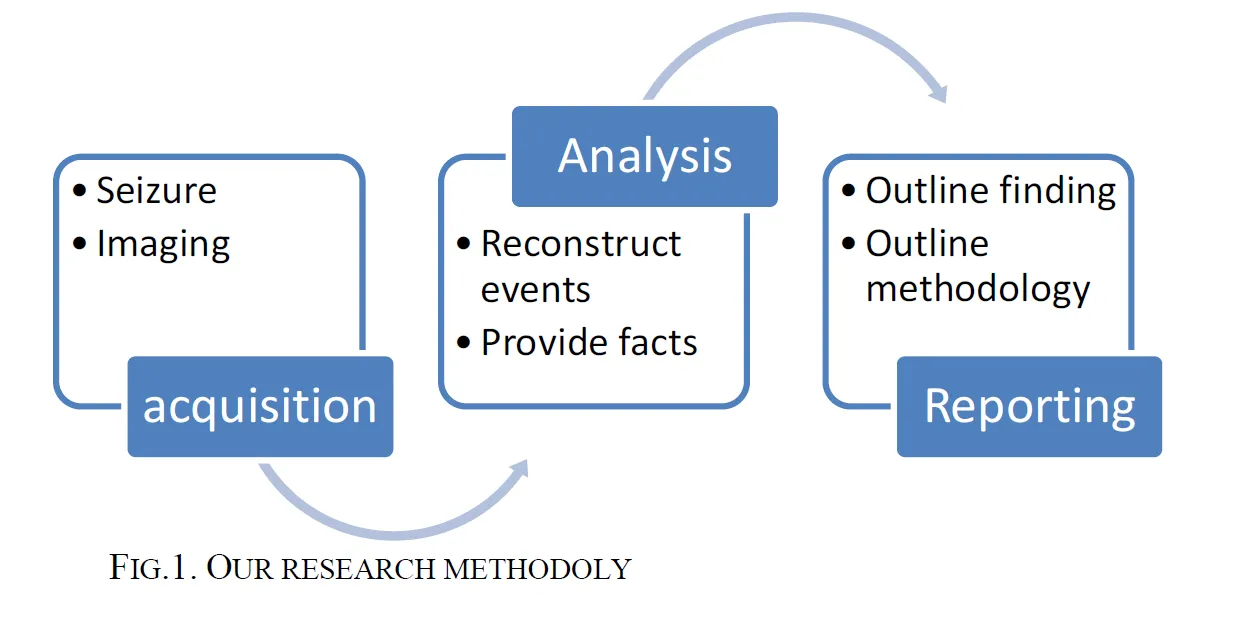

The paper is useful in defining the objectives of the investigation, which is useful for the creation of an SOP, as it clearly lays out that “The ultimate goal of the forensic investigation is to validate the requirements of a digital nonrepudiation by corroborating the drone’s ownership with the evidence of deliberate usage.” The research methodology provided backs up this idea, staying focused on the goal of the forensic investigation.

Figure 4: Research Methodology by Bouafif et al. 2018

‘UAV Forensics: DJI Mini 2 Case Study’ by Stankovi´c, Mirza, and Karabiyik 2021 consists of a case study of the data created by a specific drone. It mainly considers the data recovered from the SD card and the mobile phone used as a controller. The data takes the form of encrypted .DAT files and .txt files, containing the flight logs taken from the phone; and video and photo data taken from the SD card. Several tools are suggested during the process such as Cellebrite and Magnet ACQUIRE, which could be used to facilitate this method of data extraction, but other drone components are not examined in detail.

Standard Operating Procedure

Purpose

The purpose of this SOP is:

- to determine the owner of the drone

- to determine the purpose of the drone’s flight

- to determine what information has been collected

- With the intention of corrobating the drone’s ownership with the evidence of deliberate usage, for the sake of non-repudiation in an investigation.

Scope

This SOP includes the procedures to be taken by a first responder on the scene of a drone incident, and the methodology they should follow to ensure the data held on the drone is preserved. Also included is the actions a forensic specialist should take to extract and analyse the data for use in an investigation. The focus is on the technology used and the risks to be aware of, not on the wider administrative side that would be covered elsewhere.

Responsibilities

First Responder: Responsible for ensuring relevant data is collected from the scene and that the drone is not interfered with from the time of discovery.

Drone Digital Forensics Specialist: Responsible for extracting as much complete data from the drone as possible, and any other identified artefacts. Must maintain the integrity of the data found and keep detailed logs of any changes made. Responsible for producing a report of the findings.

Procedure

%• Detailed/specific procedure. This must include references to tools and procedures used.

First Response

The following should be completed by the first responders on the scene, who may not have the knowledge to conduct a forensic investigation but will be responsible for ensuring the data is preserved.

- Secure the area

- Ensure upon the discovery of the drone, controller, etc. the devices are not interacted with further.

- Note the time of discovery to a suitable level of accuracy i.e. to the second, UTC.

- Ensure no-one other than authorised personal are allowed on scene, and keep a log of everyone who enters and leaves.

- Video and Photograph the scene

- Use a camera that captures with exif data, ideally with location, timestamp, etc., storing the photos on a suitably sized SD Card (e.g. >4GB).

- Photograph the drone artefacts from multiple angles without moving it from the original location(s)

- Video the area to capture any details missed by the camera that may become relevant later

- Photograph the drone from all 8 points of perspective, moving it if needed, wearing clean gloves. Place on a clean plastic sheet to avoid further contamination.

- Record wet evidence

- Record the serial number, any model numbers, any QR codes, any brand indicators that could identify the drone.

- Record any evidence of modification such as labels, carried payload, obvious modifications distinct from the rest of the UAV.

- Avoid touching any wet evidence hotspots such as buttons.

- Identify data sources

- Attempt to note any obvious data sources, e.g. mounted camera; SD card; spectrometer; spectrophotometer; radio transceiver; etc.

- Note any connectors for data transfer e.g. USB-C; Micro USB; etc.

- Determine the order of volatility for the components found.

- Power off the drone according to the manufacturers instructions to avoid corrupting data.

- Place the drone into a faraday box/bag.

- Attempt to locate any other items in the vicinity -

- UAVs typically have a limited range, so look for any persons acting suspicious; discarded mobile phones; a discarded drone controller.

Data Preservation

- If an SD card is present:

- remove from the drone and secure, labelling and logging it.

- If a USB port is present:

- Attempt to connect to the drone with a portable computer

- Attempt to create an image of the internal memory, i.e. using ftk, memdump, etc.

- Get the devices to forensic analysis as soon as possible to avoid the risk of data changing due to time.

Evidence Acquisition

The following should be completed by a Drone Digital Forensics Specialist in a network shielded room.

- Prepare devices to store the recovered data - wiped SSDs of 512GB or larger.

- Place recovered devices / UAV into a network shielded room, or an area protected with wireless / signal jamming equipment

- For recovered SD Cards:

- Create an image of the SD card using a device with write-blocker capability, i.e. Cellebrite, MSAV XRY, Magnet.

- For Internal Memory

- Ideally use a drone compatible forensic tool, e.g. DJI Assistant if the drone is DJI; to extract a copy of the internal systems through a USB port.

- If there are no compatible tools available, you may consider using a chip-off method to extract the data, though this should be a last resort due to it being irreversible

- Create a backup of each image created, clearly labelling the difference between a master copy and a forensic copy.

- Create a detailed list of all images and the associated checksums, and where they were discovered. Ensure the checksums of the master copy and forensic copy match. This should be used to maintain the chain of custody.

- Import the forensic copies into a Digital Evidence Management System, e.g. Axon, AWS, NICE, etc.

Evidence Integrity Verification and Preservation

- Ensure data has not been changed

- Use dual tooling when extracting data, and compare the results/checksums for the images found to ensure data is identical to the original.

- Examine the MACs of the files found to ensure changes have not been made since copying.

- Store all files in a secure space where they cannot be modified and keep detailed logs for all discovered artefacts

- Maintain a chain of custody of all artefacts.

Evidence Analysis

A tool such as Autopsy is useful for this stage.

- Pictures and Videos

- Likely found stored on the SD card. The pictures and videos found taken my the drone can help to identify the purpose of the flight, and the usage of the drone.

- The geolocation and timestamp data found in the exif data of the images and videos may be used to recreate a timeline and flight-path of the incident. This can be viewed using an exif viewer.

- Flight Logs

- The drone should store the logs of it’s flight paths and connection to the flight controller. These are likely to be found in Internal Memory.

- If these are encrypted, attempt to decrypt them, potentially with a tool such as airdata.com, DRone Open source Parser (DROP), DatCon.

- These give details into the usage of the drone and can be used to further understand the purpose of the flight and what indicators to look for when attempting to identify the perpetrator e.g. device used to connect, location of the drone when launched.

- User Activity

- Within the data found, try to identify Personal Identifying Information about the owner of the drone.

- Attempt to find: any user logins/accounts; Wi-Fi / device connections; drone power on and shutdown times; device usage; telematic logs.

- Make a note of things that might help corroborate the drone’s ownership.

- Cloud and Remote Storage

- Data may be stored externally from the drone. Attempt to connect the drone to the location of this storage.

- If the storage server can be identified, attempt to contact the provider to potentially gain access for an investigation.

###Timeline Reconstruction

- From the media found, flight logs, and any other data recovered from the scene such as security camera footage, reconstruct a timeline of the event, considering the path of both the drone and the operator where possible. Google Earth Pro may help to visualise this.

- Correlate the data from as many sources as possible, such as: MAC information of files found; electromagnetic interference recorded in the area; connections to nearby mobile towers; etc.

Analysis Report

- The report summarising the analysis should include answers to the 5W1H questions:

- Who - identify the persons involved in the investigation

- Where - what locations were involved in the incident, from both the drone and any other associated findings

- What - what happened during the incident. Description of the facts.

- When - the times of the incident and associated events.

- Why - attempt to understand the motivation, potentially linking it to a crime e.g. stalking, drug trade, espionage.

- How - how was the incident done. What was used.

Glossary

From INTERPOL 2020.

- UAV - Unmanned Aerial Vehicle(s)

- Data - Information in analogue or digital form that can be transmitted or processed.

- Hash or Hash Value or Checksum - Numerical values generated by hashing functions used to substantiate the integrity of digital evidence

- Drone - The common term utilized to define unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs.

References

Reference listAbdulrahman Debas, E., Albuali, A. and Hafizur Rahman, M.M. (2024). Forensic Examination of Drones: A Comprehensive Study of Frameworks, Challenges, and Machine Learning Applications. IEEE Access, [online] 12, pp.111505–111522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3426028.

Al-Dhaqm, A., Ikuesan, R.A., Kebande, V.R., Razak, S. and Ghabban, F.M. (2021). Research Challenges and Opportunities in Drone Forensics Models. Electronics, [online] 10(13), p.1519. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10131519.

Alotaibi, F., Al-Dhaqm, A. and Al-Otaibi, Y.D. (2023). A Conceptual Digital Forensic Investigation Model Applicable to the Drone Forensics Field. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research, [online] 13(5), pp.11608–11615. doi:https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.6195.

Alotaibi, F.M., Al-Dhaqm, A. and Al-Otaibi, Y.D. (2022). A Novel Forensic Readiness Framework Applicable to the Drone Forensics Field. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, pp.1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8002963.

Alotaibi, F.M., Al-Dhaqm, A., Al-Otaibi, Y.D. and Alsewari, A.A. (2022). A Comprehensive Collection and Analysis Model for the Drone Forensics Field. Sensors, 22(17), p.6486. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176486.

Bouafif, H., Kamoun, F., Iqbal, F. and Marrington, A. (2018). Drone Forensics: Challenges and New Insights. 2018 9th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS). doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/ntms.2018.8328747.

INTERPOL (2020). FRAMEWORK FOR RESPONDING TO A DRONE INCIDENT For First Responders and Digital Forensics Practitioners. [online] Available at: https://www.interpol.int/content/download/17307/file/IC_DFL_DroneIncident_Final_EN.pdf?inLanguage=eng-GB [Accessed 2 Dec. 2024].

Kao, D.-Y., Chen, M.-C., Wu, W.-Y., Lin, J.-S., Chen, C.-H. and Tsai, F. (2019). Drone Forensic Investigation: DJI Spark Drone as A Case Study. Procedia Computer Science, 159, pp.1890–1899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.361.

Lan, J.K.W. and Lee, F.K.W. (2021). Drone Forensics: A Case Study on DJI Mavic Air 2. 2021 23rd International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT). doi:https://doi.org/10.23919/icact51234.2021.9370578.

Stanković, M., Mirza, M.M. and Karabiyik, U. (2021). UAV Forensics: DJI Mini 2 Case Study. Drones, 5(2), p.49. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5020049.